AFTER THE ART WAR

Hemming the Schism between Nature and Abstraction

Copyright 2009 Charles Wish

Western art in the 20th century experienced a remarkable period of evolutionary growth and change, one that could arguably be described as greater than any in its history. Yet at the same time, it would also suffer tremendous setbacks as it stubbornly clung to newfound influential leanings rife with limitation and insecurity. This essay examines how these twin scenarios of growth and restriction played out during the previous century and explores what we can do to move forward now. For it is our contention that when art becomes a divisive instrument of vanity and fear – rather than a tool of universal discovery and fulfillment – everyone stands to lose.

* * *

Forming Oppositions

This is a story about a war, which means that in order to properly tell it, we must first pretend that two things exist…where there’s really only one.

"The arbitrary division of painting into representative and decorative has put composition in the background and brought forward nature imitation as a substitute. The picture-painter is led to think of likeness to nature as the most desirable quality for his work, and the designer talks of conventionalizing: both judging their work by a standard of ‘realism’ rather than beauty."

-- A. W. Dow

In my school days, art education was still caught up in a bit of a double-bind. Formal figurative studies had been reassessed and reintroduced into the fold, while formal modernist tangents (which had once spent quite a bit of time and energy denouncing the representational camps) still held their sway. This meant that I could easily take classes from either clique, but they were often filled with an aura of sinister contempt for the infectious “other.”

I’ve long tried my best to be open to ideas and examples from both sides of this fence, but I would be lying if I pretended that there weren’t times when I struggled with the tedium of it all. While most of the collective wrangling has since fallen out of fashion, there’s still a residue of dissidence from this forced divide, one that, unfortunately, continues to obscure the broader spectrum of all painting and sculpture from now or any other time and place in history.

Even before the da Vinci days, Western theories of artistic classification regarding the stylized and the natural were being formed. Starting with some of the very first guilds, art-based endeavors were basically divided into two separate schools: representative (a naturalistic-realism approach) and decorative (a design-based approach). [1]

The first school belonged more to the painters of this time. Subjugated mostly by the patronage of the church, royalty, and various dynastic merchants, these artists were expected to produce vibrant, life-like renditions of their majestic and religious subjects without the aid of photography. With this task in mind, it was no wonder that the emphasis of their studies would focus on being able to accurately represent the rich objective splendor of the natural world.

The second school belonged more to the designers and architects. Though accountable to the same patronage as the painters, it was the responsibility of these artists, or artisans, to pare down nature to her fundamentals of line, patterns, and form. This was necessary in order to create structures, interior environments, manuscripts, and wares that were capable of evoking subjective emotion through subtler and more nonfigurative means. [2]

At the time, this division didn’t seem to present much of a problem. It was a pragmatic approach to the work of the day. What’s more, both sides respectfully understood their place in hierarchical society as fellow craftsmen and thus maintained an influential and harmonious dialogue with one another. [3] Nonetheless, as time and social revolutions went on, the patronage of the arts was allowed to shift more and more away from the church and their affiliated ruling classes to an increasingly individualistic and private marketplace. [4] This shift in economic policy would, undoubtedly, make for repercussions, some good, and some bad.

The good side was that artists and artisans were now free to stretch their aesthetic wings past the confines of timeworn academia. The backing of some guild, church, or royal subject (and all the accompanying baggage) was no longer an absolute necessity for financial success.

However, this abandonment of precepts would also mean that artists were now open to the inherent risks of self-direction (i.e. the less formal one is towards one’s training, the more likely one is to lose sight of that which is formally valuable). Because of this, art in the west now contained all the ingredients for a massive stumble. No other time witnessed the fate and truth of this circumstance more than the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

By 1848, many heavyweights in the world of art and philosophy were assertively opening themselves up to new marketable ideas, while simultaneously dismissing what they felt were the spent confines of artistic academia. Starting with movements like the PRB, the publishing of The Germ, The Vienna Secession, and, most importantly, Impressionism, rebellious exoduses from predictable studio life had now begun.

Especially in the realm of Impressionism, artistic styles and attitudes swiftly departed from their traditional origins. The hazy forests of Fontainebleau and public leisure venues, often showcasing the more taboo aspects of contemporary life, became havens where fashionable artists gathered to break free from the constraints of their studios. Their goal was not merely to capture the face of nature, but to depict how the naked eye unbiasedly perceives it. [5]

“Paint what you see, not what you know” became the foundational attitude of this bold secessionist movement – a seemingly altruistic sentiment for sure. Freed from the burden of preconceived notions and prejudices, what artist wouldn’t benefit from an afternoon of shedding their experiential partialities and taking a good, honest look at the world around them? Nevertheless, when it came to the doctrine of composition, this fairytale attitude of absolute freedom from all things old-fashioned would only lead the Impressionists into an even larger cage, biting a feeding hand, and eventually limiting the spontaneity of what they so desperately sought to spontaneously create.

Even more, theoretical composition wasn’t about to quietly submit to a revolution which sought its exclusion. Beginning with the Cubists and their experiments with the multi-sidedness of the human visual experience, which fell much in line with William James’ ideas on consciousness, questions that sought to challenge time honored norms only grew more complex. Questions like: Is referencing nature even necessary when it comes to creating moving and lasting art? Can we shift away from the Impressionists' focus on natural scenes and instead directly explore the expressive design principles of the decorative non-figured school? Fostering approaches which would involve producing paintings that abstractly represent extramaterial concepts like emotion and causation, rather than attempting to evoke such things through more recognizably concrete depictions like those of lovers or flowers. [6]

Additionally, movements like Dadaism, Expressionism, and Surrealism soon arose, only to further dismantle the foundations of conventional beliefs; some even going so far as to question the relevance of any and all artistic academia to date, especially when it came to the task of copying nature with a paint brush. Of course, many of the traditionalists at the time equated some of these revolts with artistic blasphemy, while some even resorted to fanaticism and violence to keep these “degenerate” uprisings at bay. [7] A declaration of war had officially been made.

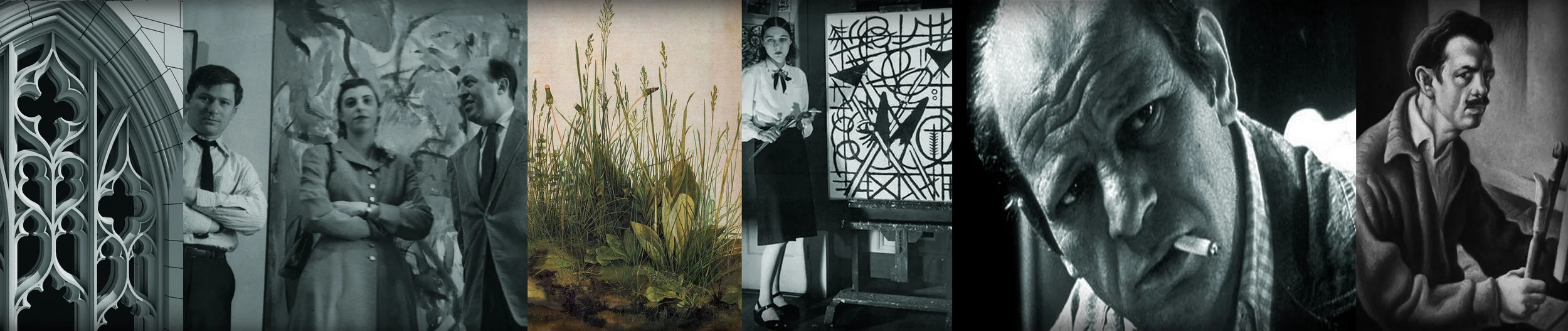

The concern of this essay, though, isn’t the politics of modern vs. conventional art or otherwise. Rather, the focal point here is how two, once cooperative, idioms of the visual artistic process, specifically when it comes to painting, became brutal enemies, and what we can do to rectify it today. Yet, before we discuss the benefits of gluing Humpty D. back together again, we should first consider his fall. A good place to start is to observe some of those who, in the very midst of this war, did their best not to separate the yolk from the white. Then take a hard look at what happened to some of them when they tried to do just that.

* * *

Regionalism & Modernism

"Conflict teaches us not to love our enemies, but to hate our allies."

-- W. L. George

Even while this war was well underway, there were those who had sincere reservations about the fight. As a matter of fact, some big names in the major post-impressionist movements such as Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, even Picasso, and Braque would all come forward during their careers with legitimate concerns about attitudes of disregard when it came to representing the natural world in art, attitudes which they themselves had once helped to foster. [8]

Cézanne summed up some of his sentiments best when he declared his goal, “…to do Poussin again, from nature,” meaning he desired to balance the best of the new schools with those of the old. [9] Nevertheless, reasonable slants like this would not hold a candle to the budding forest fire that was soon to be called abstract art and its fashionably rhetorical position that all representational imagery should be blackballed from painting. [10]

But early post-impressionist painters like Cézanne would not be the last to issue a forewarning. Some decades later, the attitude of merging classical naturalism with expressive design would again be presented as an alternative to the abstract absolutism that modernism eventually came to wholeheartedly proselytize. The often historically overlooked artists I’m now referring to were a small band known simply as “Regionalists.”

Though seen as connected with wider movements like “The American Scene” and “Neue Sachlichkiet,” and, of course, portraits of dentists holding hayforks notwithstanding, artists like Benton and Wood constructed some of the most original and influential compositions of the twentieth century. And they achieved this, not by wholly jumping on the modernist bandwagon, but also not by completely ignoring it either. Whether they were openly willing to admit it or not, these painters maintained a neutral position by pioneering what are now leading-edge principles of design – the Savanna Preference, Contour Bias, Storytelling, etc., thus creating triumphant, comprehensive images by harmonizing, not polarizing, realism with modern emotive strategies. [11]

Still, while the Regionalists were keeping busy as some of the last 20th century artists to explore the possibilities of an appealing synthesis, opposing criticism from both sides of the art debate was unavoidably nipping at their heels. This fact would have profound consequences on the fate of these painters, finally coercing them to a point where they felt the need to take sides.

Oddly enough, the first negative criticism the Regionalists received came from various members of the representational “social-realist” movement. Apparently Wood’s idyllic naturalism and Benton’s journalistic expressiveness often proved to be too demographically naïve and effervescent for the disparagingly slanted sympathies and agendas of these socioeconomically hardened painters. Brushing it off, Benton and Wood still managed to forge ahead and achieve a remarkable amount of success for their time. Yet, they were soon chastised again, only this time by the Modernists – not directly, but through oratorical implications from a popular lobby, which, once again, was against anything that appeared too overtly sentimental or 3-dimensionally naturalistic when it came to judging a worthwhile painting. [12]

No one can be certain of Regionalists’ motives; maybe they felt bitter about having to defend themselves against both camps. Maybe they were affectedly emboldened by their newfound fame. Maybe they felt that the laissez-faire attitude of the Modernists was too much for their folksy identity-politics. Maybe it was a little of all three. Whatever the reason(s), Benton and Wood decided to publicly position themselves, not with the realist camp, per-sé, but definitely against Modernism. [13] This was a rash decision, by which the major damaging fallout would be compounded threefold.

First, they took their side of the argument to sympathetic national and international news outlets, bringing this war out of the mostly sequestered classrooms, museums, and barrooms, which had hitherto been the primary arenas of debate and thrust it wholeheartedly into the public eye. Second, taken out of context, a lot of their stump-boasting felt eerily similar to that of the NSDAP, and its intolerable sentiments toward modern art. [14] Finally, and by far the worst, much of the magic in the work of the Regionalists was not autonomous of, but dependent on, the expressive principles of modern painting. By positioning themselves in this manner, they only managed to paint themselves into an ideological corner.

Conceding to an extreme case of what Robert Clagett would probably call a “not invented here complex,” these obviously cosmopolitan painters rhetorically isolated themselves from any sort of cosmopolitan venue, hence the moniker Regionalism. [15] Strictly fixing the lion-share of their focus on America’s rural parts, they would continue their freethinking experiments with nature and composition, only to increasingly find themselves compromised and stifled by one-sided statements regarding localism, artistic direction, and cultural relevance in general. Even worse, they pulled other Realists, who weren’t even part of their bucolic assertions, along with them. [16]

Swept into high-art’s indignant closet of sentimentality and nostalgia by many of his colleagues and peers, Wood ultimately felt challenged enough by these negative criticisms that he found it difficult to carry on with his former unselfconscious strength. Just before he died at age 50, he confided in Benton that he was considering a fresh start in a completely new style, a chameleon-like proposition that wasn’t entirely unfamiliar to this particular artist, but telling nonetheless. [17]

Benton would live out the rest of his days teaching and painting his way. Yet, there seemed to be a perpetual aura of bitterness about him, as he wasted much of his precious energy and time in fruitless back-and-forths with many from the ascending nuevo-art crowd. [18]

Adding insult to injury, Benton’s own pupil, Pollock, would rebelliously go on to achieve great heights within the Modernist’s opposition, not by casting aside the clumsy idioms of the Regionalists and rediscovering their initial harmonious tactics of blending the distinctly discernable with strategic patterns, but by wholeheartedly shackling himself to the chic ultimatums of the then winning, absolutely nonrepresentational 2-D camp. [19] Still, he could never completely distance himself from the aesthetic pull of Benton’s compositional teachings. [20] It was only by utilizing them, not discarding them, that Pollock would eventually become the poster-boy for both Abstract-Expressionism as well as America’s campaign to outshine Europe as the new showground for all things arty.

However, Pollock’s adamant stance against the representational would eventually take its toll, both in regards to his health and his admittedly tedious struggle to reintroduce more of the recognizable into his now, biasedly favored, nonfigurative art. [21] Unable to continue in a positive and prolific fashion, he died a tragic, depressive death at age 44, only to have his mojo soon eclipsed by the next big thing: a flashy, non-painterly style of populist appropriation that didn’t believe in bad taste and reflexively prophesized that everyone alive would one day become briefly famous. [22]

* * *

Finding a Way Out

"Sadly, it is only through extremes that mankind can arrive at the middle path of wisdom and virtue."

--Wilhelm von Humboldt

As you can see, this story isn’t a very functional one, and from here, it only got worse. With no end in sight to the bickering, heartache, and limitation, aesthetic interests and even the craft of painting itself became hesitant and embarrassingly antiquated. [23] As some of the most recognized post-mod artists went on to subject each other to a tedious gauntlet of conceptual idea mongering and licentious one-upping. [24] But, the most puzzling part of all is that the impetus behind the original conflict, which ultimately led to this questioning and near abandonment of painting itself, was based on a charade devoid of any and all reasonableness.

I have interviewed dozens of artists from all over the world (Realist, Impressionist, Surreal, Abstract/Mod, Pop, Minimal/Conceptual, Post-Mod, Installation, Performance, Photo/Vid, Graffiti, Pop-Surreal, artists who hate paintings but love sculpture, artists who love color but hate tone, artists from the country, artists from the city – the list of identifiable diversity goes on and on). And, when the chips were down, not one of them could ever look me in the eye and say, “My art has improved so much now that I’ve decided to absolutely omit any semblance of the figurative wonders of nature.” Nor could anyone say, “I just created the most brilliant thing, and it’s all because I cast all the abstractions of compositional design to the wind.”

Human experience possesses an unbroken, formless potential for manifesting form just as much as it does a different, form-filled potential for returning to unmanifested formlessness. We tend to find meaning and enhancement in our visual environments by representing the formless through abstract design and the formative through figurative simulation. However, our endeavor to emotively communicate with shapes and abstract signifiers has never been unproblematic; there is no universal color for laughter, texture for sorrow, or pattern for apathy, and of course, the same goes for the tangibly recognizable.

Yet, the effort to pit compositional design and figurative-naturalism against each other, in painting or any other form of artistic expression, certainly didn’t make the adventure any easier. Actually, I think it’s safe to say that this attempted disunion may have been one of the biggest cultural hindrances of the twentieth century; the snares of which still haven’t been fully understood or disabled. [25] These two elements have been, and always will be, symbiotic counterparts – friends, not enemies.

Highbrow vs. Lowbrow

Making matters even worse, what started out as a pragmatic rift about how to generate better art, eventually compounded itself into yet another way to quarrel over cultural politics in general. The exact definitions of high and low culture have been debated for quite some time. [26] And the all-too-human tendency to seek out and detain aesthetics and artifacts that support our values and ideals when it comes to upper and lower social-status divisions is a significant part of the dysfunctional divisiveness that occurred here.

In this regard, two of the most outstanding personalities involved in the cultural wrangles of the previous century (i.e. Pollock and Benton) are both classic examples of the follies that can occur when it comes to navigating highbrow vs. lowbrow tensions. Benton, a cosmopolitan going out of his way to pose as a yokel, and Pollock, a provincial going out of his way to pose as a sophist, were strongly tethered idealists. [27] Not in the way academia has often accused them, but idealists nonetheless. How so? Both of them desperately wanted to live in a world free of the unequivocal pretentiousness of manufactured cultural superiority and dictatorship, all while being praised as dictators for doing something culturally superior – a fantasy that will never occur.

Like many, by succumbing to this sort of impractical idealism (while subconsciously aware of the victor-less battle they were waging), both of them (either by vying to become an outstanding member of a current pedestalized club or by creating a whole new position) fell into the never-ending trappings of compromise and dissent. However, art doesn’t care one bit about these hierarchical musings. Moreover, courting a thing like art to propagate our own limited notions of identity and cultural predominance is one of the worst foundations we could ever attempt to build an artistic relationship upon.

That’s not to imply, however, that by not taking up such a culturally political stance, anyone can make great art. But, if the titans of the 20th century had realistically lightened up a bit and viewed their work as primarily service-oriented rather than ego-oriented, I would wager that what they produced would likely have been all the more effective.

In a tutelary world where culture is equally serviceable to either role (i.e. all of us are students, and all of us are teachers) who should we consult with and/or profess to? The folks up at the university on the hill, or the folks down the street sculpting logs with chainsaws? Why these questions persist and to what practicality they serve is something only you can answer for yourself. Just know this: whatever regarding conclusions one may reach, if they’re the type of ideas which attempt to compartmentalize and culturally ration your subject matter by labeling it universally superior, or even worse, universally inferior, you’re liable to be working in the wrong direction.

Even so, as we examine many of the painterly factions emerging in the late 20th and current 21st centuries, it’s plain to see that many are willing and able to recalibrate their artistic compasses and cast aside any combative remainders of doubt, even if some of our prominent institutions still fail to support them. [28] Painters usually heal quicker than academics and critics; they have to because they’re the ones who are actually making stuff. And when the last remaining stalwarts of this “art war” finally find the wisdom and character to confess the sins of the past century, they’re going to discover that a whole bunch of initiators, at the beginning of this century, already did it for them, and that makes me smile.

* * *

Notes:

[1] “Composition: Understanding Line, Notan & Color,” Dow, J.M. Bowles Publishing, Boston, 1899, pgs. 4 & 44.

[2] “The Story of Art,” E.H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press, 1995, pgs. 248-252.

[3] “I, Michelangelo”, Illetschko, Prestel, 2004. pgs. 109-125.

“History of Art,” Janson, Harry Abrams Inc. 2001, pg. 258.

[4] “The Story of Art,” E.H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press, 1995, pgs. 409-533.

[5] “The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists,” Chilvers, Oxford Press, 1990, pg. 373.

“The Impressionists With Tim Marlow,” (documentary film) Written By: Marlow, Directed by: Grabsky, Distributed by: Seventh-Art, 2009.

[6] “The Story of Art,” E.H. Gombrich, Phaidon Press, 1995, Pg. 574.

“History of Art,” Janson, Harry Abrams Inc. 2001, pg. 776.

“The Principals of Psychology,” James, 1890, Harvard University Press, 1983.

[7] “The Rape of Europa,” (documentary film) Written By: Berge & Nicholas, Directed by: Berge & Cohen, Distributed by: Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2007.

[8] “The Shock of the New,” Hughes, Random House Inc., 1980, pgs. 112-163.

[9] “The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists,” Chilvers, Oxford Press, 1990, pg. 87.

[10] Avant-Garde & Kitsch, Greenberg, Partisan Review, 1939.

“Benton, Pollock & The politics of Modernism,” Doss, University of Chicago Press, 1991, pgs. 311-358.

[11]“The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists,” Chilvers, Oxford Press, 1990, pg. 385.

“Grant Wood, An American Master Revealed,” Roberts, Dennis, Horns & Parkin, Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995, pg. 19

“Universal Principles of Design,” Lidwell, Holden & Butler, Rockport Inc. 2003, pgs. 62, 212, 230.

[12] “The Definition of Neo-Traditionalism,” Maurice Denis, 1890.

“Parnassus,” Volume XII - Number 8, Longman, 1940.

[13] “Grant Wood, A Study in American Art & Culture,” Dennis, University of Missouri Press, 1975, pg. 144.

Time Magazine (cover story) “U.S. Scene,” Christmas Eve, 1934.

[14] “Renegade Regionalists,” Dennis, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998, pgs. 69-89.

“Grant Wood, A Study in American Art & Culture,” Dennis, University of Missouri Press, 1975, pg. 10.

“The Rape of Europa,” (documentary film) Written By: Berge & Nicholas, Directed by: Berge & Cohen, Distributed by: Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2007.

[15] “Grant Wood, A Study in American Art & Culture,” Dennis, University of Missouri Press, 1975, pg. 150.

[16] “Grant Wood, A Study in American Art & Culture,” Dennis, University of Missouri Press, 1975, pg. 146.

[17] “Grant Wood’s Studio,” Milosch, Prestel, 2005, pg. 29 “A Short History of American Painting,” Flexner, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950, pg.99.

[18] “Ken Burns' America: Thomas Hart Benton,” (documentary film) Written & Directed By: Ken Burns, Distributed by: Public Broadcasting System, 1988.

[19] “To A Violent Grave,” Potter, Putnam Publishing Inc., 1985 pg. 204

[20] “To A Violent Grave,” Potter, Putnam Publishing Inc., 1985 pg. 150.

[21] “History of Art,” Janson, Harry Abrams Inc. 2001, pg. 814.

“To A Violent Grave,” Potter, Putnam Publishing Inc., 1985 pg. 225.

[22] ]“The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art & Artists,” Chilvers, Oxford Press, 1990, pg. 367.

“American Art, a Cultural History,”Bjelac, Harry Abrams Inc.,2001, pgs. 367-372.

[23] Baldessari’s Commissioned Paintings, 1969, Molly Barnes & Richard Feigen Galleries.

[24] “The Shock of the New,” Hughes, Random House Inc., 1980, pgs. 385-387.

[25] Huffingtonpost.com, posted January 5, 2012. "Carmen Tisch Charged With Criminal Mischief After Punching, Urinating Next To A $30 Million Clyfford Still Painting.”

[26] “The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography,” Thackara, Sunrise magazine, October 1999–February 2000, Theosophical University Press.

[27] “Tom & Jack,” Adams, Bloomsbury Press, 2009, pgs. 240-244.

[28] “Art Talk,” kcrw.com, posted July 21, 2012, “Should Art Schools Ignore the Art Market,” Edward Goldman.

updated January 2025